For many the city of Lezhë is mainly associated with the Albanian national hero, Gjergj Kastrioti, known as Skanderbeg, who famously formed the League of Lezhë in the city in 1444, an alliance of lords who came together to rise up against the Ottoman occupation and which led to twenty five years of bloody resistance to the occupying forces and the armies sent by, and often led by, the Sultan. It was also the place where Skanderbeg was laid to rest following his death in 1478, and where a monument to him now stands at the ruined Cathedral of St Nicholas.

However, the city was also very important in ancient times and Lissus (as it was named back then) has substantial archaeological remains from the Illyrian and Roman periods. It’s a great place for a short visit as you can see both the Skanderbeg monument and some of the Illyrian and Roman remains in a park by the side of the river Drin, but if you have more time and are feeling more adventurous you can drive up to the acropolis of the ancient city and visit the citadel which, though it has been rebuilt many times, still has visible sections of wall from the 4thcentury BCE when Lissus became urbanized.

The key to understanding the ancient city is its strategic location. It lies on the bank of the river Drin which was navigable in ancient times, and is just 3 kilometres from the Adriatic today. The city sits on a limestone spur, an excellent defensive position with 360 degree views enabling sight of all approaches to the city. The hill to the east (Mal i Shëlbuemit) was known in ancient times as Acrolissus (high Lissus) and it is here that the earliest remains of habitation have been found, including traces of walls dating to the 8thcentury. However, it seems that by the 6thcentury the population had moved to the lower hilltop to the west and settled there[1]. Not only was the city on a navigable river and therefore accessible from the Adriatic but it was on several important land routes, including into Kosovo. We don’t know much about the inhabitants of the city, except that Lissus was in the territory of the Labeatai, an Illyrian tribe whose territory was around Lake Shkoder (then Lake Labeatis). Lissus may have been its most southerly extent.

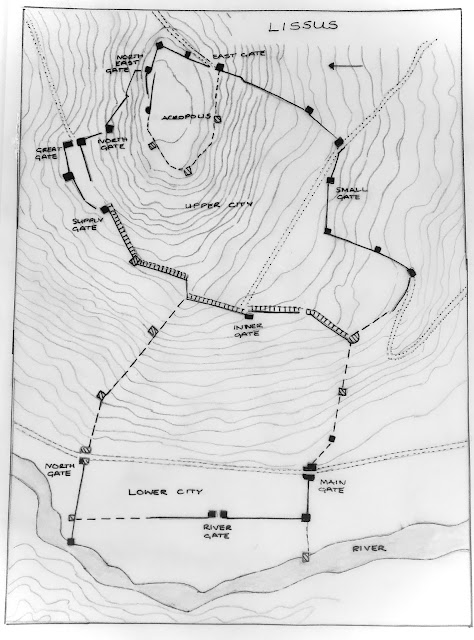

The summit of the hill was first enclosed by walls in the 6thcentury BCE, but in the 4thcentury, a time when many of the Illyrian settlements became urbanized, a circuit wall with gates and towers was built. The wall was built using the emplecton technique where two parallel walls are constructed and the core between them is filled with rubble or other infill. The outer surfaces are faced, the inner roughly finished. Every few meters a large block is placed crossways between the two outer walls for stability. We can see from the stretches of wall that are still standing how effective this was. The huge blocks of local limestone fit together beautifully and do not need any mortar to hold them together. Some of blocks and courses are slightly offset, an anti-seismic technique. Corners of the walls often have a finely worked edge, perhaps to make the lining up of the blocks more accurate. By the time of urbanization in the 4thcentury, the settlement had grown beyond the acropolis and there was a lower city along the bank of the river. In response to the need to protect both parts of the city, and also to ensure that the upper city had access to the river the walls were extended down the hillside enclosing the lower town with a gate on the river and linking the upper and lower parts, enclosing an area of about 22 hectares.

Sections of the walls are still visible incorporated into the later walls of the citadel on the acropolis, in a ruined state on the sides of the hill, and excavated in the lower town. The walls are nearly 2.5 kilometres in circuit, and include 11 gates of various sizes and techniques. It is common in Illyrian and Epirote defensive walls of the 4thand 3rdcenturies to combine different types of gates within a circuit depending on terrain and access. Defensive towers, of both round and square type, protect the corners and long stretches of the wall, once again adapting to the terrain at each particular point. Some of the network of ancient roads can be discerned, both inside and outside the walls. There is a particularly well-preserved section of road visible in the lower city, passing through the so-called ‘main gate’ and under the Skanderbeg monument. The ‘main gate’ is an excellent example of defensive architecture of the period. It is a double gate, with grooves and sockets for outer and inner doors, and projecting rectangular towers of two storey height.

|

| The 'Main Gate' |

The important strategic position of Lissus meant that it was a target, not only for Rome, but for the Macedonians during their wars with Rome. Lissus is mentioned for the first time in historical sources by Polybius, in the 2nd century BC, in his account of the Illyrian wars and the Macedonian-Roman wars between 246-146 BCE. The harbour was used by the Illyrian Ardiaei tribe as a base of the Illyrian navy in many of the attacks against coastal cities of the Adriatic and beyond which were a provocation to Rome, and eventually perhaps the excuse they needed to cross the Adriatic.

Polybius tells us that Philip V of Macedon took Lissus and Acrolissus in 213 BCE to secure a route for Macedon to advance down the Adriatic coast. The city was retaken by King Gentius of the Labeatai, and hosted a delegation from Perseus, the last Macedonian king, in order to sign an alliance between them in the face of the threat from Rome. The Romans eventually defeated Gentius, himself the last of the Illyrian kings, and occupied southern Illyria. The Labeates were taxed by Rome and Lissus, because of its important strategic position, continued to flourish as it became an important naval base and military and administrative centre. The city grew again during the Roman period, and was granted the status of municipium by Julius Casear - it had been loyal to Caesar during the civil war against Pompey, and Marc Antony had landed his forces at Shengjin. Fragments of amphorae from around the Mediterranean conjure up images of goods being unloaded at the quay of the river Drin, and inscriptions tell us about the administrative roles of some of the occupants of the city. Excavations by a joint Albanian-Austrian team in the lower city have revealed that the city expanded beyond the walls during this period. The remains of an atrium-style Roman residence with a small bath can be seen by the main gate, and later occupants had taken advantage of the water supply and ready building materials to convert the building into a church.

The city remained an important imperial regional fortress and the fortifications were again repaired by Justinian. The 6thcentury repair of the acropolis is borne out by excavations of the French-Albanian team’s analysis of the human remains. Burials in and around the remains of the church within the acropolis date from the 6th/7thcentury to the 14th.

In medieval times the city passed variously from the Dukagjin family, to Serbia, and to Venice, under whose patronage Skanderbeg hosted the meeting of local lords that culminated in the League of Lezhë. It was taken by the Ottomans in 1498 and sacked, but refortified by Sultan Selim I at the beginning of the 16thcentury. The fortress on the acropolis was rebuilt, and a mosque built on a high point within the citadel. The mosque’s minaret would have been visible from the valley sending out a powerful message, just as Skanderbeg’s beacon had done for so many years in the previous century.

|

| Plan of the acropolis |

Further Reading

Brunga, Liza, Lissus, the city of 12 gates, Éditions universitaires européennes, 2017

Lehner, Manfred, Lissus Excavation Report 2004, University of Graz 2004

Malaj, Edmond, Lezha Gjatë Periudhës së Antikitetit, Studimi Historike 2017, 3-4, Tirana 2018

Etleva Nallbani, et al., Lezha [Lissos, Alessio] (Albanie), Chronique des activités archéologiques de l’École française de Rome, Balkans, 2016.

[1]There has been some confusion about the origins of the city, since Diodorus Siculus writing in the 1stcentury BCE his Library says that Dionysius of Syracuse founded a ‘city named Lissus’ in 385 as part of a strategy to secure Adriatic trade routes, but there was clearly an Illyrian settlement in existence before this date. It is possible that Diodorus was confusing Lissus with the island of Issa, which was indeed founded by Dionysius.

I think this is among the most significant info for me. And i am glad reading your article. But should remark on few general things, The site style is great, the articles is really nice : D. Good job, cheers. Car service from Rome to Ravello

ReplyDeleteValuable information. Lucky me I found your website by accident, and I am shocked why this accident didn't happened earlier! I bookmarked it.

ReplyDeletecar service from FCO to Ravello